L.Park: You are a composer and organist, what approach do you have as a musician when you compose?

Grégoire Rolland: I have an approach that is global, one of a composer, meaning that I need to think music in its entirety with all of its settings. But I also have the approach of an interpret: it’s the link between the two that is so interesting to me, being between the composer and the organist.

It’s this link that I try to create between the thought of music, its scheme, and the writing of a score — because I am not from a oral tradition — so it’s really the architectural work of a score which will be interpreted.

By the way, I often have surprises, because sometimes when we think about things, we tell ourselves: “it’s going to be great!” and when we finally play it, we actually understand that we have to modify a lot of things. And other times, there is also a link between the composer and the interpretation, because as a composer, you are so focused that you can’t see the whole picture, as you are constantly working on your score.

When the interpret comes in, they have a clear vision of what they want, but sometimes this vision is almost too narrow. Yet, they also can provide a new concept. And that’s something that I really enjoy: I love being at the same time, the composer and interpret, because it allows me to follow the entire path of a piece’s transmission, from its creation to its release to the public.

So, I situate myself between all of these different sides of the coin. I’ve always been fascinated by Asian culture, because of its richness.

L.Park: Which artists influenced you?

Grégoire Rolland: Like I was saying, It’s not really the artists that inspire me but I read a lot of things, and I have a lot of interest for Chinese culture. For example, I wrote a piece for piano inspired by Lao-Tseu, I composed around Confucius, Sun Tzu and a lot of other writers and philosophers.

I also wrote around Japanese songs and Korean culture. But, more than the artists, it’s really the culture, in a sense that I am highly interested in Chinese philosophy, the way of thinking, the language. For me language conveys, of course, philosophy, the Chinese and Asian way of interpreting life as a whole.

I truly experimented Asian culture, through my wife, who is Chinese. I started spending time in Chinese culture, and more generally in Asian culture, every day. It really opened me to a new world, in an artistic and cultural way, but also through language and history. It’s 5000 years of culture, and it’s a completely different philosophical approach, etc. So little by little, I started to write through a new lens.

But this language, it transpires through the writing, and for me, it’s a complete entity.

I worked a lot on the relationship between the language and the tones in Chinese. Because it is a tonal language, it’s already a musical language on its own in a way.

The link between writing, calligraphy, ideogram, etc and how I can project all of this into a piece, a music that would be unique to me.

For example, in Shēng, an a cappella piece for six women, I started from the word itself. Throughout the piece, I unfold the word and I explore all of its sonic possibilities. I work on the problematic of tone: because it’s a flat tone, it’s almost singing a sound of Shēng: it’s already sung in itself.

In my work, I also touch upon calligraphy: how this word is written, line by line, and by coding it into my musical form. So it’s in fact a cultural development a little more global than only being inspired by an artist or a work of art. Here, it may be to go deeper into the Chinese language and culture.

L.Park: Talking about calligraphy, how to do code it in your work?

Grégoire Rolland: There are various ways of approaching it. For Shēng I really used the different lines: the horizontal ones represent the melodies and the vertical ones are link to percussions or harmony.

L.Park: Why percussion?

Grégoire Rolland: Because if we take a white noise’s sonogram — which is most of time from a percussion of everyday’s life (it can be anything, not just an instrument labeled as a percussion) — we can see that the sonogram is vertical. So I told myself: “Why not take this scheme and put it in relation with the ideogram?”.

There are other forms of coding possible, especially in a graphic point of view, in the score. So a line that starts in a horizontal manner can only be in the score, graphically: I will work voice by voice to have something more horizontal, with voices appearing little by little, etc.

L.Park: So what is the link with the graphic notation from contemporary music?

Grégoire Rolland: There are some elements of the graphic notation in my work but it’s not my focus. Because for me, it would be almost too simple to only work on that aspect: I only have to take the ideogram, line by line, and to project a graphic point of view to then give to the interpret, who makes it their own.

We would also be in an almost improvised music, as in many graphic notations. But I think that I needed to further code this work around graphic, more or less.

L.Park: How unique is it to compose for an organ?

Grégoire Rolland: The organ is an instrument which is tough to tackle on. (Many composers are afraid of it by the way, because there’s no organs which are alike.) Therefore, we have to write for a specific organ and we have to have humility in a way: to accept that on another organ, it’s going to sound completely different. And that’s something quite tough, to tackle on the good method to write for this instrument.

As a composer, you have to be highly precise by thinking “I want that type of tone, that type of technique, that blending”, because you also talk in terms of color: the organ is an instrument of colors. So, you have to try to keep in mind all of this and at the same time, after you finish the piece, to take a step back and to accept that it’s going to sound in a complete different manner on another organ.

So maybe that’s the issue with this instrument, because they’re all built in different ways.

L.Park: Why can they sound differently? It is linked to the “type of organ”?

Grégoire Rolland: Yes, it is linked to the types of organs, because as I said earlier, they are not built in the same manner.

First of all, there’s various instrument-builders who worked on organ in different ways. It also depends if it’s a baroque organ, a neo-classic organ, romantic, modern, symphonic…

But it’s also due to the fact that those instruments reside in different places. So the resonance of the organ, for example, varies depending on which church it resides in.

The placement, the perception, the distance will also be different.

Sometimes, when an organ is on a little chapel, it’s not going to sound the same as in a big cathedral. So it’s all of that which creates the settings that are each time divergent.

L.Park: Does the approach change when you compose for an orchestra or a choir?

Grégoire Rolland: Of course, because all of these ensembles that you are talking about are highly rich in tones, and full of possibilities.

The voice is a complex instrument, rich with a multitude of possibilities for sound treatment. As for the organ, it has various playing techniques, from the different sound fields that we can have, etc. And the orchestra, of course, has a lot of instruments.

So, at the same time, it’s a great richness for all three. But I was talking a little about the organ and about the fact that you have to accept that it will always sound different.

For me, the orchestra is completely different: because, on the contrary, we haves tones that we can rely on: we know how woods or metal in wind instruments sound like. Even if, of course, the acoustic changes according to the concert halls and the instruments’ brands.

But globally, there’s an approach maybe more precise of tones, their blending and textures in an orchestra compared to an organ. And that’s an element that intrigues me a lot. Finally, when I write for an orchestra and that I am in front of it, I don’t have a lot of surprises with my compositions.

Because I spent a lot of time working on the textures, the blending of the tones, the orchestration, to think about it internally, to hear it. So, when I find myself with the orchestra, I know what I want and how it’s going to sound. It’s something that sometimes, with the organ, is more complicated.

There are some scores for organ where, finally, I put some nuances in, and it’s the organist job to understand them. Because it depends so much on the organ that I told myself “it’s useless: I am going to write this, to ask for that type of playing, and then it’s not going to sound as I expected”.

So at the end, I worked at times on the sound field for the organ, unlike for the orchestra, where I focused on the tones, etc. As you can see, it’s very different approaches. For the voice, it’s not really the same.

As a composer, I love to have a lyrical technique for singing, as it’s an important part of the voice for me: it’s one of its constituants, as the other one is percussion. There are two elements that allow us to talk and to have languages. It’s really consonants and vowels. So I work a lot on these mixes and by differentiating the percussive from the singing.

You can hear that type of work in the track Shēng or Lü (for twelve voices, a cappella), it’s a piece where women sing in an opera way while the men do the percussions with their voices, the roles are then reversed to ultimately blend together. So as you can see, I am fully into this vocal and percussive exploration, but in a certain way, you can also work on tone like in an orchestra. And at times, I can even do a correlation between a vocal percussion and an instrumental one that you can find in an ensemble. For example, one vocal percussion can be written as a tom drum, etc.

L.Park: How do you transcribe percussions in the voice?

Grégoire Rolland: First of all, I would say that it’s by working on spectral and tone analysis and how to blend them. Then, you have to explore all the vocal possibilities in front of you: imitate a cymbal with or without a drum brush, etc. You also have to try to find various codes between those two types of percussions (vocal and instrumental).

L.Park: In your pieces, you blend two sounds: one from Asia and one from the West. Both of those musics differ a lot from each other, especially by the use of music modes. How do you blend them into your music?

Grégoire Rolland: So, there are musical modes that overlap between Western and Asian cultures. What I like, is to take a little from the settings of each culture and to create a sort of hybridization. So, to develop a sort of new sonic culture.

I wouldn’t have the pretension to construct a culture based on point of view, but to find new sonic elements: some from Asian culture, other from West culture, and to create a type of sound that is unique.

For example, we can take the work of Claude Debussy, Maurice Ravel or Henri Dutilleux and think, because of the way it is orchestrated: “it’s French”. But they are sounds from Asia put into their pieces: it’s a hybrid sort of music, and that’s what I’m seeking. Therefore, if people can’t really perceive what’s from the West or Asian culture in my work, then it means that I did a good job.

Now, if someone tells me “we can tell that you use the pentatonic mode here”, and that in consequence, it sounds Asian, then to me that signifies that I failed at my job. To me, the goal is not to copy a culture and to create a subculture: cultural appropriation is a complex subject that you need to pay attention to. It’s not harmless, we need to respect all cultures: whether if it’s ours (the West), Asia’s or any culture for that matter. I think that from the moment we develop an interest for another culture, we need to respect it, always.

L.Park: Do you have a particular manner to apprehend the spoken-sung technique that you use in Audite Caeli?

Grégoire Rolland: I see which passages you are speaking about, what you need to know is that in the score, everything is written, note by note. But there is no spoken-sung technique: it’s just that, for me, I am bringing it closer to a musical gesture. Consequently, I write my gesture like I would write one for the flute or any other instrument. There is what we call the rocket: something that starts from a sort of lyrical takeoff, I write it out in its entirety for the singer — it’s up to them to actually sing those notes, or at least give the impression that they’re going to sing every single note.

And it’s not always the case: for the recording, we had a hard time on one or two sentences, where the singer was trying to sing all the notes, and he was really shy because he was scared of messing it up. And due to that, the musical gesture wasn’t working. I said to him: “Forget the notes, you know them, you have them unconsciously in your voice, in your ear: sing the phrase without asking yourself questions and it will come naturally”. After he freed himself from that anxiety, it worked.

I also write in a way that is clear, so that the singers know which pitch to sing and at the same time, it’s anchored in expressivity and in a musical gesture. For me, those two elements are objects which are indeed, a little spoken-sung.

When you take a closer look to this musical gesture principle, you can see that we are close to Schoenberg with his work Pierrot lunaire. So I don’t invent or re-invent anything: I use with parsimony those types of elements to create real musical gestures and expressivity.

L.Park: What is the difference, and maybe the stakes, between creating a piece in live and to recording it?

Grégoire Rolland: Recording is really constructing an object which will be able to leave a trace for future interprets or listeners who wish to experience it once more. But this important trace doesn’t replace the creation, the interpretation of a piece in the moment — in an instant manner with its flaws — and a form of simplicity while sharing it with the audience.

This answer is also as an organist, it’s not the same thing when we are going to give in the moment a vision of a piece that is probably going to be imperfect, with maybe some noises from the public, that are also going to be a part of this music.

Finally, when we “freeze” a performance, it’s not enough. For example, I worry that an interpret would spend their time listening to my pieces in order to perform them, because for me, it’s a bad idea. Having an overview by ear is good, but then you need to believe in yourself as an interpret, to let things happen and to have your own vision of the piece: it wouldn’t be false. It’s not because a certain version is recorded that it’s the reference to base your work on: we really have to be careful about that. They are also a lot of performers that re-record pieces at different times in their lives, and I think it’s a beautiful approach.

L.Park: In this album, you use a lot of dissonance, whether by Gregorian chant, blending medieval and contemporary music, or by the organ. Does it have a specific purpose?

Grégoire Rolland: I personally don’t think when or how I’m going to write dissonance in a score: I guess it just comes naturally, because it’s a tool for a composer. You know, a composer is someone who has a lot of tools in their bag and who use those depending on what we need to express: it’s like a craftsman.

The composer, is an artist because they have an artistic vision, an inspiration but also a craftsman who works with the tools at their disposition. They are going to use specific tools, a little like a cabinetmaker who’s building beautiful furniture: first, they have the vision for it and then they make it something that is creative.

At the end, it’s a little like that as a composer: dissonance is a tool among others.

And you’re right about that link with Gregorian chant: I love to use it because it allows me to create a sort of figurism, for example in the piece Caligaverunt oculi mei.

So we can have all at the same time: Gregorian chant, dissonance and tension.

The question about tension-release is that notion of dissonance and regarding the Gregorian chant, dissonance helps to project it in the contemporary world of today.

It allows to take something from the medieval period and to make it something that’s current.

But consonance is also a great tool, and for that, I come back to the notion of tension-release. Most of the time, dissonance is linked to a form of tension, and consonance to a form of relaxation: this was greatly understood by the Franco-Flemish School or Bach.

Therefore, dissonance is an essential tool to create an expressive music and it’s this expressivity that I’m seeking. There are other uses of dissonance: it can be the tune of the tones for example, here you don’t think about dissonance related to consonance, but more for itself. This helps to create a texture, a sonic experience that we never heard before. So there’s no need of being scare of it in a certain way, I think that I use it to enrich my language and to write the music that I want.

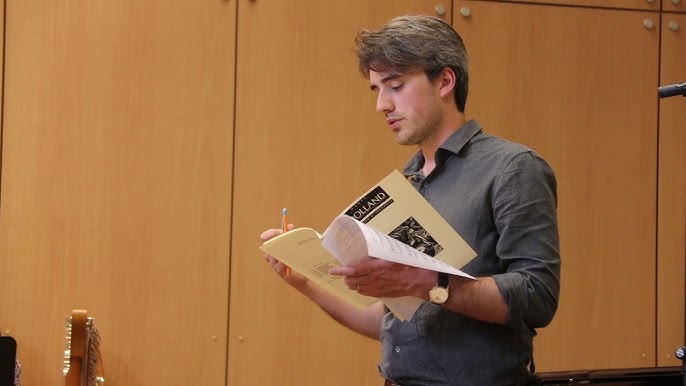

Photo © Guillaume Esteve

Leave a comment